PEACE IN THE MAKING

By September, 2018, leaders of the warring factions in South Sudan signed a peace agreement. It was due for implementation in May, 2019. That was deferred to November, and then to February 2020. Finally, state sponsored hostilities had ceased. Old Fangak wasted no time taking advantage of the peace. You see, the river between Juba (the capital city) and Old Fangak became safe for travel. Trader boats could transport goods and passengers.

The Alaska team planned a TB building about 8 years ago, but logistics were impossible. With peace imminent, the impossible began to look like a possibility. They sprang into action last summer, designing and organizing our amazing new facility. One ward isolates those with sputum positive TB, so they don’t infect others; another shelters those with spinal TB, whose “broken backs” make walking difficult. They ordered the custom-made prefab building, and had it delivered by boat.

Housing for new sputum-positive patients has become essential. Old Fangak is now a town. We used to hold clinic under a tree, where breezes blew away most of the germs, and let patients find an isolated hut or tent for shelter. Now there are no uncrowded places left. Patients must be isolated for the first few weeks of treatment to avoid spreading TB around the community.

AND THEN CAME COVID

Jill left Old Fangak on March 3. She returned to Bethel, Alaska, to work some shifts – but her true motivation was to welcome little Leo when he came into the world. Leo’s mom, Ashley Fairbanks Glasheen, is a nurse practitioner who began her medical career by volunteering in Old Fangak during the 2011 kala azar outbreak.

Leo arrived March 7. Jill had two more weeks of work in Bethel. Then came COVID. The pandemic was declared, Jill’s flight was re-booked, and cancelled, and re-booked . . . Then the Juba authorities visited our logistics man one night to advise him, “Don’t let Jill fly. We really won’t be able to get her in.” The next day they shut the border. The eye clinic we’d organized for February was canceled because some eye team expats worried that fighting might break out again when the unity government was installed.

Patients arrived, but the eye team didn’t. We booked a smaller eye clinic in April, staffed mainly by South Sudanese. This too was finally cancelled, because how could you keep all the elders waiting in Old Fangak, when no one knew what the pandemic might permit? Some people had huddled there for a month already. They returned home, still blind, awaiting their next opportunity.

Other logistical matters have also turned into nightmares. With peace, supplies could come in by truck from Uganda. That was easier, and much cheaper than flying stuff in—until one day they asked all drivers to wait for COVID tests—and that was four weeks ago! The line of lorries now stretches back for 24 miles! Our plumpy nut sits somewhere in that line.

BACK TO TB

We are still welcoming lots of new TB patients. TB treatment reopened just north of us in Malakal, which used to be the second biggest city in South Sudan. It was almost flattened by the fighting. We are so fortunate in Old Fangak to have never had to close the clinic in the 20 years since we opened.

We still have trouble getting people tested for HIV, but we are happy that we can offer co-infected patients treatment for both diseases. Many are so sick, and their TB is disseminated (spread throughout their bodies), not confined to lungs or spine or lymph nodes.

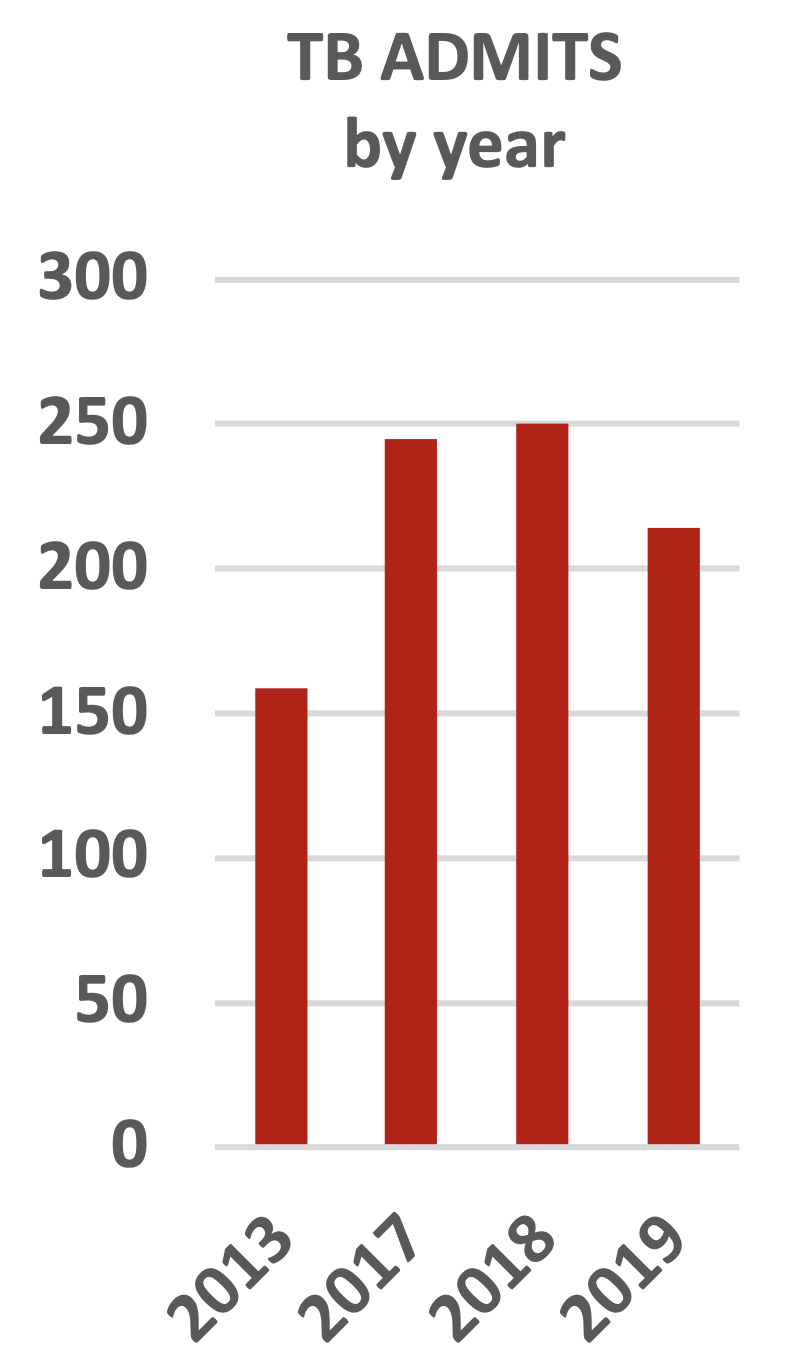

The slight decline in total TB patients is really nice to see. It may due to the fact that some patients can now be treated in Malakal.

Dr. James Wal graduated from the highly-regarded Methodist University in Kenya and recently joined our staff in Old Fangak.

WE HAVE A SOUTH SUDANESE DOCTOR ON STAFF!

Dr. James Wal graduated from the highly-regarded Methodist University in Kenya. American Mission Healthcare, which has supported our project for years, paid his school fees. After James completed five years of schooling, plus his internship, the organization he planned to work with had departed South Sudan. AMH contacted us to see if we had room for a doctor from the state just across the Nile, with the same “mother tongue”.

Oh my gosh, what an opportunity! Everyone is happy. SSMR staff love having a local guy who can doctor, with or without Jill on site. MSF deemed him competent already, and have him share their night call. Patients see him as one of their own. With school now open in town, he may inspire our kids to dream of new careers.

HOW TO SAVE LIVES IN SOUTH SUDAN

Worldwide causes of death are grouped into 3 broad categories: injuries, non-communicable diseases, and the one we focus on— infectious, maternal, neonatal and nutritional disease.

These graphs, from Our World Data, show trends over the past 27 years.

RED for communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases.

BLUE for non- communicable diseases.

YELLOW for injuries.

Worldwide, 50% of deaths come to people over the age of 70. In South Sudan, 52% die age 14 and under.

We started Sudan Tuberculosis Project to treat the world’s most lethal infectious disease, in a remote roadless setting complicated by civil war. We soon added treatment for kala azar, which later eclipsed TB as the biggest infectious killer in our area. But you can't ignore malaria--brucella--everyday pneumonias--leprosy. Family doctors see it all.

When we were overwhelmed with war wounded in 2014, Medecins Sans Frontiers (Doctors Without Borders) sent a team to help with casualties. Then thousands of displaced people required more services than we could provide. MSF expanded their role to share the burden of infectious, maternal/perinatal, and nutrition issues.

Our evening fever clinic is a constant. Scattered headlamps illuminate little islands of doctor/patient interaction in the courtyard. Our patients may have walked all day and arrived after dark, or may have illness that declares itself when the sun goes down and fevers go up.

Kala azar, our particular area of expertise, is incredibly well controlled at the moment. In crazy 2011, we treated 5000 patients—half the cases in South Sudan. This year, we only admitted 100. With field research into treatment protocols, we have shortened the regimen of daily injections from 30 to 17 days. New protocols for intercurrent illnesses, and transfusing anemic patients before their haemoglobin falls desperately low, has helped decrease kala azar mortality from 9% to 1%. We are grateful.

EXPANDING INTO CHRONIC DISEASE MANAGEMENT

Most of our local folk are skinny. Disease makes them even skinnier. Their goal is to eat enough to keep flesh on their bones, not to control their weight.

Then comes a local man who moves to the city, and finds a sedentary job, and plenty to eat. He gets chubby. He dies of a heart attack. All of a sudden, our community begins to think that the easy life is perhaps not so good.

Bit by bit, we talk to our staff about walking, even if you do live next to the market. (Whoever thought you would need to encourage nomads to walk?) People request nicotine aids to stop smoking.

As more of our community survives childhood, and childbirth, some live long enough to develop chronic disease. Diabetes, hypertension, asthma, renal failure—all those plagues of Western life. They are still novelties in South Sudan. But we are expanding our program to teach national staff about diseases that need to be prevented through public health education, rather than treated with antibiotics. Having Dr. James on board provides continuity in that effort.

OUR HAPPY STORY

SSMR covers maternity two days per week, and lends a hand when asked. One day this fall, we were called for a delivery which just kept on going. The midwife was working with Baby Number One, handing Baby Number Two off to Jill for resuscitation—but there was more! Dr. Jenn appeared just in time to help catch Baby Number Three. Three little girls, soon healthy and howling.

When Mom went into heart failure two days later, SSMR could provide ACE inhibitors and nitrate, since we carry meds for chronic disease. She pulled out of failure. Then the family figured we should supply supplemental milk for the next three months. (In case you were wondering, no baby in Old Fangak wears diapers. Moms are so attuned to their movements that they hold babies out and let them pee on the ground. But can you imagine doing that with triplets?!) We treated maternal, neonatal, and nutritional issues for that family—as well as what could easily become a chronic, life-threatening disease for the mom. Amazingly, not one got an infection!